Click here for a printable version of the analysis

Nick Murray, Policy Analyst

J. Scott Moody, Chief Executive Officer, Granite Institute

KEY FINDINGS

-

Today, inflation-adjusted General Fund spending per Maine resident is $3,108, the highest on record. Over the last 10 years, real spending on Maine’s General Fund has grown more than 20%, while the state’s population has grown by only 1.66%. If lawmakers kept real spending on pace with population since 2010, per capita spending would be $2,626. Taxpayers would have spent 18% less ($550 million) on the General Fund in the current fiscal year alone.

- By the end of 2020, Maine had lost 50,000 jobs and 20,000 workers had left the labor force.

- Childless, able-bodied adults aged 19-49 make up more than 70% of Maine’s Medicaid expansion population. The state could save $70 million by limiting expansion to those 50 and older and slow the main driver of ballooning MaineCare costs (11.7% in two years).

- There are more than 34,500 fewer public school students in Maine than in 2001, a 16.7% drop, yet inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending is 70% higher.

- While Maine’s projected biennial budget shortfall is not as deep as was expected in August, the state must prioritize economic growth over government growth. Government cannot be the cart pulling the horse. It must leave room for the private sector to drive future growth.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the economic shock from the global coronavirus pandemic, made worse by the responses of many state governors, should be of paramount concern to present and future policymakers. As public officials fixated on a single pathogen, broad restrictions intended to slow transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, inflicted their own damage on society. These harms will be felt for many years, not merely in economic terms, but to overall public health and happiness.

Divided into two main sections, this series offers a blueprint for a financially sustainable economic recovery, taking into account the most recent forecasts from the Maine state government. The first section seeks to quantify the damage experienced by the Maine economy over 2020 and predict, with as much confidence as possible, when it will rebound to pre-pandemic levels. The second section provides solutions to cover the expected revenue shortfall in the state’s next biennial budget and seed a future of economic growth.

Part 1: Understanding the Economic Impacts of the Pandemic

FORECASTING MAINE’S ECONOMIC FUTURE

The truly unprecedented economic shock from broad-ranging government orders to shut down businesses, schools, gatherings, and elective medical care in response to the pandemic, was reflected in immensely volatile monthly unemployment and tax revenue data. Given a long period of relative stability, this makes modeling a recovery course with confidence very difficult.

Another factor that makes long-term economic forecasting challenging at this juncture is the uncertainty about when and how the overall labor force will rebound. If Maine sets a goal to return to “full employment” (somewhere around 2.5% unemployment), but other pandemic-related structural shocks persist through 2021, it is unlikely that employment will rebound in the next five to ten years. The Maine Consensus Economic Forecasting Commission (CEFC) also recognizes this, projecting that total employment will not reach 2019 levels at least until after 2025.

LABOR MARKET & EMPLOYMENT

In April 2020, the first full month of “nonessential” business and travel shutdowns in response to the spread of COVID-19, nearly 1-in-10 Maine workers applied for unemployment benefits. This figure was even higher than the 8.3% unemployed at the nadir of the Great Recession of 2008-09. More than 16% of Maine workers employed in January 2020 were no longer employed in April. Even by December, 20,000 fewer workers were participating in the labor force and the state was still down more than 50,000 jobs in the year.

The unique nature of this economic slump makes the unemployment rate an unreliable data point to track the recovery, so this report looks at projections of total employment. A recent slowdown in the number of jobs in Maine and nationally, as noted in November and December data, could mean that this recovery will be more elusive than current estimates suggest.

The severe shocks to the labor market from the spring shutdown have been compounded by the structural demographic problems that have plagued Maine for at least the last decade. Since 1970, Maine’s average age increased by 56% to the highest in the nation: nearly 45 years old. In a 2015 report from the University of Maine and state Department of Labor, researchers estimated that Maine’s “working age-to-senior ratio is expected to decline from an already low 3.4 in 2015 to 2.2 in 2030.” Mirroring a similar national trend, this effect on Maine’s population and workforce is expected to be worse than the United States’ average due to flat or negative population growth.

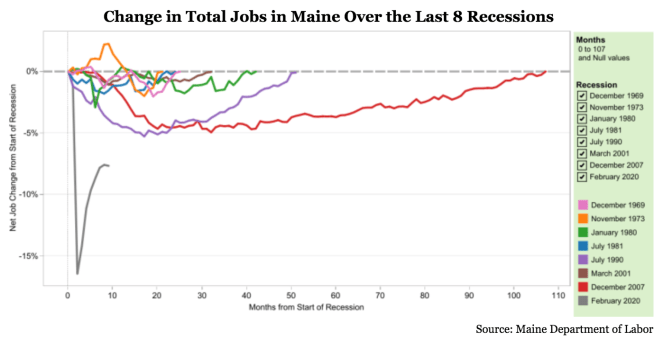

It took the Maine workforce nearly 10 years to recover from the Great Recession. With a population and labor force that does not look much different today, this recovery could take at least that long. The CEFC understands this very real possibility. That is why it recommended the state put 18% of General Fund revenues, the maximum amount allowed by statute, into the Budget Stabilization Fund (BSF) “to fully offset the revenue declines from a moderate recession.”

Federal policy responses have also contributed to the overall inflexibility of the labor force. A paper from researchers at the University of Chicago points out that perverse incentives under expanded pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) from the CARES Act made adjustments more difficult for workers and employers. The program initially gave every unemployed worker $600 per week, designed to replace 100% of the national mean wage when combined with mean state UI benefits. As a result, two-thirds of recipients brought home more than 100% of their usual earnings; the median rate was 145% of earnings.

Authors of the University of Chicago study propose altering emergency UI assistance to a percentage of wages, instead of a weekly lump sum, in order to avoid policy that could “hamper efficient labor reallocation…during an eventual recovery.” Unfortunately, this program was not reformed, but extended as part of the most recent federal spending package, providing $300 per week per recipient. President Joe Biden has proposed raising this weekly unemployment bonus benefit to $400 in his stimulus plan released mid-January. Congress passed additional relief legislation in March 2021 that includes a $300 pandemic UI benefit.

EFFECTS OF THE PANDEMIC & MAINE’S RESPONSE

A survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics from the beginning of the pandemic in March through the end of September 2020 asked employers all over the country how 2020 affected their operations and workforce. Maine’s results were largely consistent with national trends on how many businesses were forced to close by government mandate (16-18%) and those who had difficulties shipping goods during the pandemic (11-12%), but differed slightly when measuring supply and demand.

More than 40% of Maine businesses reported experiencing “a shortage of supplies or inputs,” slightly exceeding the national average of 36%. Only three states had higher reported shortages. This may be balanced out by the higher-than-average reports of those who experienced demand increases over the pandemic. More than 18% of Maine businesses reported increased demand, the most in the country.

As a result of the pandemic and government responses in 2020, Yelp estimated in September that 60% of U.S. small businesses that closed by the end of August would not reopen, a national total likely exceeding 100,000 businesses. This rate is very likely to be higher for those businesses which rely on a robust summer tourist season to make a profit and pay employees, investors, and creditors. Those firms largely operate on thin margins and cannot make up losses as easily as other sectors. Small businesses make up over 99% of the Maine economy, and employ over 56% of the workforce. Applying Yelp’s findings to the BLS survey results, Maine Policy estimates that up to 9% of Maine businesses closed in 2020.

There are some positive indicators as well. Census data show that business applications in Maine are up over 9% year-over-year from Q4 2019 to 2020. Official state data on changes in business designations are only released in January of every year. Those show the number of active Maine businesses grew by over 6,000 from 2020 to 2021. This signifies that entrepreneurs are beginning to reorganize and reorient their resources to more valuable uses. Overall, applications have been rising steadily in Maine since 2016 and seem to be returning to their pre-pandemic pace, after the uncertainty of the 2020 spring and summer.

Weekly data show that “non-store” or online retailers made up nearly 12% of all business applications filed nationwide in 2020, showing a tendency for many entrepreneurs to look to the virtual space for their next endeavor. Non-store retailers made up more than 71% of all retail business applications. Non-store retail employment in Maine has been on a steady decline since its peak in 2006, but the economic shakeup from the pandemic and resulting surge in online business applications could help Maine buck that trend.

HOSPITALITY & TOURISM

What’s unfortunate for Maine is how much the state depends on leisure and hospitality to drive the economy during the summer tourist season. Accounting for 9.4% of total employment, Maine is more dependent on this industry than many of its regional neighbors: New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire. It is possible that this dependence could lead to a greater loss of businesses than estimated.

In 2016, the US Census Bureau reported that 78.7% of workers in Maine’s “accomodation and food service” industry were employed by small businesses, meaning those with 500 or fewer employees. The dominance of small businesses in the scope of the Maine economy could also contribute to later-than-expected losses, as small businesses incur larger start-up costs that can take much longer to recoup than franchisees. This means that it will be difficult for many of the small, tourism-related businesses Maine lost in 2020 to bounce back.

Maine’s tourism, hospitality, retail, and entertainment sectors have been hit the hardest in 2020. Over 60,000 Mainers were employed in hospitality and tourism in the second quarter of 2019, the beginning of the summer season. Measuring the effects of the pandemic-related shutdowns, the industry lost nearly 20,000 jobs from February to November 2020. This is a rosier picture than June, when more than 35,000 tourism jobs had been lost since February, but still accounts for 40% of Maine’s total job losses in 2020.

The Maine Office of Tourism (MOT) estimates that 1 in every 6 jobs is linked to tourism. In 2019, the industry contributed over $2.8 billion in income to Maine households and nearly $650 million in tax revenue for state and local governments. At $6.5 billion per year, tourism makes up more than 10% of the state’s total economic output.

The Maine Office of Tourism (MOT) estimates that 1 in every 6 jobs is linked to tourism. In 2019, the industry contributed over $2.8 billion in income to Maine households and nearly $650 million in tax revenue for state and local governments. At $6.5 billion per year, tourism makes up more than 10% of the state’s total economic output.

Visitors from Canada alone spent almost $1.2 billion in Maine, making up more than 14% of all overnight stays in 2019, but since March 18, 2020, the international border with Canada has been closed to nonessential travel, including tourism and recreation. In May, year-over-year border crossings were down 88%. The Maine economy receives an outsized economic impact from Canadian tourism; in 2014, Maine attracted the 7th-most Canadian visitors of any state.

Bureau of Economic Analysis data show that businesses classified either as “arts, entertainment, and recreation,” or “accomodation and food services” lost 17.5% of their personal income from Q1 to Q3 2020. In the same period in 2019, these sectors grew just over 1%. Fortunately, the retail sector rebounded from its bottom in Q2 2020, growing personal income by 8% over Q1-Q3 2020. Retail earns more income than the arts and accommodations sectors combined. If retail is included in what is considered tourism, it helped the overall drop in personal income by only 2.9% over Q1-Q3 2020, contrasted with a gain of 1.78% over the same period in 2019. But, retail is also difficult to tie directly to tourism, especially in 2021, since so many new retail businesses applications are for “non store” or online retailers, and thus not linked as closely to “Vacationland” visitors.

A reason that a retail rebound might be more robust versus that of arts and food services is that, once the lucrative summer season passes, hotels cannot backfill their rooms. Restaurants cannot make up for lost patrons, either due to depressed demand or government restrictions that prevent them from filling their establishments. Those businesses that rely on out-of-state visitors missed untold income from the multitude of cancelled vacations to Maine over 2020. Some businesses, like those in manufacturing or retail, have the potential to make up for past losses with higher productivity or more working hours in the future. Others, like restaurants and recreational tours, cannot recoup these losses once their season is over.

Maine’s tourism workers, especially in arts, entertainment, hospitality, and food service, continue to struggle to recover their lost income from the 2020 spring and summer shutdowns. Sadly, in yet another misguided and heavy-handed approach to COVID-19, Governor Janet Mills ordered a statewide curfew of 9:00 p.m. for public-facing food and drink service, which began on November 20 and continued until February 1. While providing no metrics to determine the success or failure of this policy, this move likely led to significant reduction in earnings for service businesses and their employees over the winter holiday season.

Research linking viral transmission to restaurants is inconclusive, but that didn’t stop the Mills administration from forcing these rules on already-struggling Maine workers.

As seen in the Yelp data, business closures slowed significantly in the early summer, but began to climb again in July, with more permanent closures among them. Could this show that the continuation of pandemic-related restrictions on businesses throughout the summer meant that fewer and fewer businesses could hang on into the fall? The Bangor Daily News recently reported on the growing open restaurant spaces in Portland, denoting a 26% increase in restaurant closures across the state’s largest city since October 2020.

Effects of “nonessential” business shutdowns will be with us for many years. Governor Mills’ executive orders that forced Mainers to stay at home unless their employment was deemed essential created a stark divide between those who could afford to stay home to help “flatten the curve” and those who could not. “Pressing pause” on the economy knocked traditionally-stable supply chains completely off-kilter. Due to shortages of household staples like meat, flour, and toilet paper, combined with Maine’s anti-price gouging law, grocery stores were forced to limit purchases to prevent hoarding.

Continued and sustained mandates on businesses throughout the summer and fall also contributed to depressed economic confidence. Requiring public-facing businesses to limit capacity, install barriers, and police the governor’s universal face covering mandate meant that many had to reallocate labor to managing compliance, while trying to appeal to a pandemic-weary customer base. Even though the Maine economy has recovered about half of the jobs lost since the economy bottomed out in April, a June study suggested that 60% of those losses were the result of heavy-handed state action, not the virus itself.

The decimation of Maine small businesses this year—especially within the tourism and hospitality sector—will affect the lives of many thousands of workers. State budgets must reflect this fact and move to encourage more private-sector job creation. Government may only spend that which it has taxed from the people who have created value for others. In order to move the state on a path of opportunity, economic growth must be driven by industry, not government.

Restrictions on events and gatherings and their concomitant enforcement persist despite adequate empirical evidence to suggest that they have worked to suppress or eliminate viral spread. Unfortunately, because of this, Maine is likely to see a long, slow recovery, especially among tourism-related industries.

BUDGET IMPLICATIONS

In order to return to a level of economic adaptability and vitality needed for growth, state leaders must recognize that Maine’s business owners should be trusted to serve their communities and support the lives of their employees. Governor Mills’ constantly shifting, arbitrary, and often draconian executive orders issued and reissued during the year-long Civil State of Emergency have done much more damage to Mainers’ lives and livelihoods than COVID-19 has wrought. The virus carries a serious disease, and for some, severe illness and death. This should not be understated, but by refusing to trust the people to care for each other while making a living, the current administration has done enormous damage to Maine’s future.

For many months, Governor Mills lobbied Congress to allow the use of federal pandemic relief funds as “revenue backfill” in order to fill gaps in tax revenue resulting from her orders to shut down and restrict business. After more than six months of negotiations, Congress declined to send more aid to state and local governments in the massive $2.3 trillion stimulus-plus-budget bill signed by former President Trump in December. Perhaps Mills has found a more receptive audience with President Biden, but with unsustainable levels of federal debt, financial solvency should be key for Congress as well.

In September, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued a report projecting that the United States’ national debt would reach 98.2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by the end of 2020. Most recent estimates as of March 2021 peg the national debt at over $28 trillion, nearly 130% of GDP. If including unfunded federal liabilities, the nation owes nearly $160 trillion.

Instead of begging for another debt-fueled bailout from Washington D.C., Maine politicians should look inward and make the hard choices necessary to right-size government spending amid a persistent recession. Balancing budgets on the backs of everyday workers and business owners through higher taxes and fees, instead of meaningful spending cuts, is a strategy of the fiscally tone-deaf.

Part 2: Finding Budget Solutions

PROJECTING FISCAL YEARS 2022-23

Negotiations between Governor Mills and the members of the 130th Legislature will determine how the state will cover a projected two-year budget shortfall of just under $400 million. This represents the most recent projections of state forecasters at the CEFC and Revenue Forecasting Committee (RFC) for the upcoming biennium, spanning fiscal years 2022 and 2023 (FY22/23).

Projections have trended better than expected. Current shortfall numbers are less than half of those in the RFC’s August report, which projected Maine’s General Fund would be down more than $500 million in FY21 and more than $800 million over the FY22/23 biennium. With this positive news, there are more paths for lawmakers to achieve a balanced budget over the next biennium. Overall, the FY22/23 budget should look to revitalize Maine’s labor force and business environment, while balancing the needs of the most vulnerable.

The following sections are presented as a slate of options for lawmakers to meet this goal; a menu of policy choices to either reduce current spending or expand the economy to drive state tax revenue growth.

In September 2020, Governor Mills’ issued a curtailment order to cover $222 million of the $422 million General Fund shortfall projected for FY21, ending June 30, 2021. Part of the order allowed the state to save $125 million through adjusted federal Medicaid reimbursement rates, frozen vacant positions, delayed technology updates, and foregone travel. Mills’ latest proposal for the upcoming FY22/23 biennial budget, released in January, continues these various cost-saving measures where applicable, but the administration’s creative accounting leaves more questions than it answers.

While Governor Mills insists that her budget proposal contains “no drama,” a deeper examination shows the administration is putting off implementing the reforms necessary to recover from the worst economic recession since 2008. Mills has signaled to taxpayers that she will do everything to maintain (and if possible, raise) current levels of government spending, when she should be making the hard choices necessary to fix Maine’s structural economic issues.

For example, Part P of the Mills administration’s budget proposal raises the staff attrition rate from 1.6% to 5%, assuming that more than triple the number of state employees will voluntarily retire or leave the state workforce than expected. Is this accurate accounting, or simply wishful thinking? If too few state workers retire over the next two years, this line alone could bust open a nearly $30 million hole in the budget, requiring substantial cuts to programs or staff in other areas. This calculation does not take into account long-term costs of retaining a larger public workforce than the state can afford, stressing the state’s pension system and bond rating. Governor Mills and her budget officers would be wise to make these sorts of decisions now rather than hope that they don’t become a problem in the future.

The numbers of state and local government workers in Maine has decreased more than 11% over 2020, with local governments taking triple the losses of the state workforce. While this is a significant reduction overall, lawmakers should not see these as losses, but instead factor them in as a cost of an economic downturn. Ensuring long-term stability in the budget and pension system is critical. Maine state budgeters should look for other serious, structural changes that will position Maine’s economy to grow quickly out of the current malaise.

When attempting to right-size the state government after a year of vast economic uncertainty, the most significant cost-saving measures will not be found in one-time accounting fixes, but rather the state’s largest agencies like the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which oversees MaineCare, Maine’s Medicaid program. Other policy reforms are also necessary after a harrowing year. Some may directly result in budget savings, but all carry the potential to facilitate economic growth instead of government growth.

Ultimately, state leaders cannot expect to spend their way out of this slump. They must look for potentially unconventional solutions to fortify Maine’s economic resilience and adaptability in the wake of 2020. The key to this strategy is the understanding that reforms to reduce economic barriers to prosperity will ultimately help the least-advantaged in society.

Maine people should be confident that the state will not impose itself onto the daily efforts of workers and business owners attempting to serve their communities and earn a living. To this end, the restrictions that have besieged the Maine economy, implemented unilaterally by the governor and without legislative input, should be lifted post haste. People deserve trust and a presumption of liberty from their leaders.

REFORMING WELFARE

When attempting to address the largest cost drivers of Maine’s state budget, one must look at state spending on welfare programs. While legislators and Governor Mills are not facing a shortfall as deep as originally expected, it is prudent to review the largest programs in the budget in the shadow of the 2020 economic slump, as this is where the greatest savings are likely to be found. Below are various cost-saving options that Maine Policy believes would help right-size Maine state government and encourage greater overall labor force participation.

While many of these reforms touch on Maine’s welfare benefits system, it is important to prioritize the thousands of truly vulnerable people who are not able to support themselves without help from the state. These reforms will not affect those for whom these programs are vital, but rather those who are able to work. Combined with removing onerous regulatory barriers, Maine could incentivize business and job creation, opening doors for thousands who are currently trapped in a cycle of poverty and dependency.

As a percentage of total spending, Maine spends more on public assistance than 44 states, more than any in New England, and nearly double the national average of 1.2%. Maine spends more on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program than 46 states, as much as California and New York, and more than double the national average of 0.7%.

During the LePage administration, the state set a 60-month lifetime limit on families accepting TANF. As a result, more than one-quarter of recipients left the program. A 2017 report from the Office of Policy and Management (OPM), which studied a cohort of 1,856 TANF recipients before and after the change, noted that the total wages of these individuals more than doubled from 2011 to 2012. Maine can still do more to build on this progress: limit this benefit for the truly needy and stem the tide of dependency that generous welfare programs can incentivize. Phasing down the lifetime TANF limit to 48 months could empower 10,000-20,000 individuals to leave the TANF program and pursue the dignity that comes with gaining personal financial stability. With $131 million total spent on TANF in 2019, this reform could save Maine’s General Fund up to $10 million over the biennium.

As of 2018, 16.8% of Maine residents received benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as food stamps, the third-highest rate in the nation. Dubiously, Maine also has the second-highest food stamp error rate in the country at more than 19%; nearly one-in-five SNAP payments were made in error. Because of this high error rate, Maine taxpayers must reimburse the federal government about $3 million over the next biennium. There are likely many options to control costs, such as aligning Maine’s rates to national and regional averages. National and New England averages for SNAP participation are around 11%, with an error rate of about 7.7%. Legislators should call for an audit of the SNAP program to better understand why Maine’s SNAP program performs so poorly compared to the nation.

Empowering individuals to lift themselves and their families out of poverty should be a key goal of policymakers. Unfortunately, Governor Mills’ proposed budget does not set a goal to reduce the number of Mainers dependent on welfare benefits. Research shows a strong relationship between unemployment and depression, so any progress made toward a healthy economy and vibrant job market means ensuring a healthier future through sustainable prosperity.

MEDICAID & MEDICARE

In one of her first acts as governor, Mills implemented an expansion of MaineCare, Maine’s Medicaid program, after it was approved by voters in November 2018. MaineCare is an important public health insurance program that provides medical care to more than 320,000 Maine adults and children living in or just outside of poverty. However, its growing budget has crowded out other spending priorities, threatening Maine’s long-term fiscal stability.

As a percentage of its budget, Maine spends more on Medicaid than any other state in New England. In 2018, the percentage of state budget funds dedicated to MaineCare accounted for 34% of Maine’s total expenditures, or slightly more than one-third of all state spending. Spending on MaineCare increased by 6.4% from 2017 to 2018, then 5.3% more between 2018 and 2019, meaning that MaineCare spending has increased by more than 11.7% in the two years since voters approved Medicaid expansion at the ballot box.

Since the beginning of 2019, the expansion population has grown to more than 73,000 Mainers, of which more than 84% are childless, able-bodied adults. The Office of Fiscal and Program Review (OFPR) noted that MaineCare cases had been decreasing as January 2019 approached. That trend continued for traditional Medicaid populations until the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Even during the pandemic and its aftermath, the caseload of the expansion population has grown significantly faster than traditional Medicaid patients, a nearly 50% higher rate of growth.

In September 2020, a representative from the OFPR confirmed to the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Appropriations and Financial Affairs that Medicaid expansion has been the largest cost driver within Medicaid over FY20.

OFPR reports that overall MaineCare spending rose by $280.1 million, or 9.1%, from FY19 to FY20. Approximately $250 million of that increase—or 88.3%—came from Medicaid expansion. Over those two fiscal years, taxpayer liabilities for Medicaid expansion exceeded $361.5 million. Amid a confluence of public health and budgetary crises, there is no doubt that the traditional Medicaid population should be the priority to receive MaineCare benefits before childless, able-bodied adults.

MaineCare is a healthcare program designed for the most vulnerable Mainers, not for those with no dependents and who are able to work. These adults should be participating in the labor force, and participating in the private market for health insurance. State leaders, to shore up potential budget gaps and minimize harm to the most needy, should instruct DHHS to freeze new cases with a goal of entirely removing all childless, able-bodied adults from the program.

A Kaiser Family Foundation study from 2009 showed a direct relationship between unemployment and Medicaid case rates, finding that with every 1% increase in the unemployment rate, the Medicaid caseload rises three-quarters of a percent. There is no substitute for a healthy economy, and while Maine should provide a safety net for those who truly cannot support themselves, providing benefits to able-bodied adults without children (especially those under 50 or 60) could have a significantly detrimental effect on labor force adaptability.

Limiting access to healthcare during a pandemic seems harsh, but it is important to understand that the state’s response to the pandemic, in the form of economic and societal shutdowns, carry their own suite of costs on individual well-being. Mental health is clearly linked to economic independence. Lawmakers must look beyond the short-term thinking of the last 12 months and chart a vibrant future for Maine.

By capping enrollment in Medicaid Expansion at current levels (around 70,000 cases), Maine taxpayers could save an estimated $50-100 million on MaineCare over the next biennium. This could be partially achieved by imposing MaineCare work requirements which Governor Mills deauthorized before implementation early in her term. Given that more than 80% of the expansion population is made up of able-bodied, childless adults, and over 70% of those are between the ages of 19 and 49, simply by limiting expanded MaineCare eligibility to those who are aged 50 and older, Maine could save nearly $70 million. By removing all childless, able-bodied, working-age adults from MaineCare, taxpayers could save nearly $250 million over the biennium.

Including federal dollars, which account for nearly two-thirds of the state’s spending on Medicaid, Maine offers $300 more per Medicaid recipient than the average U.S. state and the average of other rural peer states like Vermont, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Arkansas, and Iowa. Maine taxpayers could save nearly $32 million over the biennium by aligning benefit rates for all Medicaid recipients with those of other rural states. If only instituted for the expansion population, leaving overall eligibility rules unchanged, taxpayers could save $5 million.

To shore up funds for Maine’s most needy citizens, lawmakers should continue to redirect funds from the Fund for a Healthy Maine (FHM) to essential MaineCare services. Seeded by payments from the multi-state tobacco settlement, the Fund has received more than $1 billion in total, and spent more than $215 million since its creation in 1998. It received over $65 million in FY21 alone.

FHM largely funds efforts to discourage smoking among adults and children, but with little discernible results. Rates of smoking and tobacco use overall have been falling steadily since the 1970s, and will continue to do so, with or without state-funded marketing campaigns. These funds should go to where they can do the most good: providing direct healthcare to Maine’s most vulnerable populations.

There are many paths to budget savings through Medicaid reform. The missing variable is political will. By tackling some of the suggestions laid out here—restricting eligibility to the truly needy, aligning benefit disbursement rates to peer states, and making better use of existing funds—Maine lawmakers could deliver savings to taxpayers in excess of $250 million over the biennium, and ensure the state is not holding back the productive potential of working-age adults.

CUTTING UNNECESSARY OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING

Any regulation that hinders the entrance of workers or entrepreneurs into the marketplace, without significant public health or safety benefits, should be abolished. Lawmakers should heed the recommendation of the governor’s Economic Recovery Committee to review regulatory barriers and streamline processes where those barriers inhibit prosperity.

For instance, over-burdensome regulations on caregivers and rules for child care facilities have distorted the availability of affordable child care in Maine. Child care is a foundational service to ensuring a stable economy for Maine’s working parents and dual-income households. Early in the pandemic, Governor Mills eased some rules on Maine’s child care providers by allowing family child care providers to watch three (instead of two) children, aside from those living in their home, without certification. By making these changes permanent in statute, lawmakers can do much to cut red tape and aid struggling young families in the post-lockdown economic slump.

Occupational licensing reform is not a new idea for Maine. In 2013, the OPM highlighted numerous professional licenses that the state could repeal with only “minimal” financial impact, since licensing fees do not flow to the General Fund. OPM also noted that doing away with these programs and boards “would not jeopardize the health, safety and welfare of Maine citizens.” Ending needless licensing for jobs like arborists, dieticians, interior designers, soil scientists, cosmetologists, and other occupations would substantially lower barriers to work for thousands of Mainers.

In March 2020, the Commissioner of Professional and Financial Regulation submitted a report to the legislature upon studying barriers to licensing and credentialing for foreign and out-of-state workers. The report noted the “need to simplify in language in licensing statutes…for those who may wish to use their skills at a lower level while earning the credentials or experience necessary to earn a Maine license.” Lawmakers should pursue more ways to help workers moving to Maine from inside or outside the United States to practice their occupation as easily as possible.

Repealing rules that do not markedly enhance consumer health and safety, but rather delay or restrict opportunity, will likely stimulate significant economic growth. Research from the Cato Institute found that occupational licensure “has significant negative effects on occupational mobility when switching both into and out of licensed occupations,” noting that “licensing can account for at least 7.7 percent of the total decline in occupational mobility over the past two decades.” Holding on to outworn licensing regimes can stifle the economy. Workers and entrepreneurs will be better equipped to redirect their resources when onerous rules no longer get in the way of their pursuit of happiness.

Cutting down Maine’s overall occupational licensing regime to a reasonable size will not affect expected General Fund revenues since licensing offices are operated through fees obtained from licensure. The state could achieve some cost savings by reducing total staff needed to administer its various licensing programs. For instance, eliminating licensure for dietitians, barbers and cosmetologists, transient salespeople, funeral attendants and directors, massage therapists, and occupational therapists, taxpayers could realize at least $1 million in immediate savings from state employee salary cuts. Far from the only benefit, cutting needless licensing regimes will spur more opportunities for Mainers to start successful careers and contribute to the tax base.

In her spring 2020 emergency orders, Governor Mills also suspended physician oversight requirements for advanced practice nurses and physicians assistants, and expanded the ability of healthcare workers to provide telehealth services. With these actions, the governor greatly helped Maine people get access to needed care during the pandemic. If these temporary changes did not lead to negative patient outcomes, these rules on medical providers should be permanently undone as well.

ELIMINATING CERTIFICATE OF NEED

During the spring of 2020, Governor Mills issued various executive orders that loosened healthcare regulations during the Civil State of Emergency in response to COVID-19. For instance, she allowed for an expedited process for Certificate of Need (CON) applications, a usually lengthy and costly process required of any hospital seeking to significantly expand its capacity. Lawmakers should consider ending the process altogether, as doing so would ensure greater responsiveness in the health care sector in the event of a drastic public health crisis.

Eliminating Certificate of Need in Maine would not amount to significant budgetary savings. A manager at the Division of Licensing and Certification (DLC) within DHHS estimated that processing CON applications requires about one full-time employee in the office. While sparing Maine’s medical providers from this costly process wouldn’t help the biennial budget, it could accelerate growth in the supply of healthcare. Myriad research supports the view that CON laws depress competition and lead to worse outcomes for patient health and satisfaction.

Not only that, eliminating CON would Maine save hospitals, nursing homes, and other healthcare providers millions of dollars in application fees. From 2018 to 2020, DLC processed 18 CON applications, accumulating a total of $348,786 in fees, an average of nearly $20,000 per application. Without this added cost, these facilities will be better equipped to invest in their workers and services over the next biennium and beyond.

In a pandemic or public health emergency where hospital capacity is closely watched, government should get out of the way of medical providers and allow them to offer care where and when the need arises.

K-12 EDUCATION

Education is the cornerstone of society, as it helps to cultivate the future workforce and culture, but also because it stabilizes a parent’s ability to earn a wage from day to day. This is even more apparent as attempts to adapt to the pandemic by traditional public schools have been hit-and-miss. Could it be a coincidence that record numbers of American parents are saying that they want more choice in directing their child’s education?

The widespread closures of schools and separation of young Mainers from their peers over the last year caused its own pandemic-related shock throughout the state’s education system. Thousands of teachers and students across Maine were thrust into unfamiliar and unstable situations, having to use untested remote or hybrid learning models in order to make it through the school year. Unfortunately, thousands of Maine students are still caught in limbo today, but many have begun to opt-out of traditional schooling altogether.

In June, the Maine Department of Education reported the ranks of homeschooled students grew 10.5% from the year before. From 2008 to 2014, that number had remained relatively stable: around 5,000 students. Since 2014, homeschool enrollment has grown nearly 35%. Clearly, parents are craving more options than their assigned district school.

After the 2019-2020 school year, Maine public school enrollment dropped by 4.4%. Falling total enrollment is a decades-long trend for Maine, with 34,563 (16.7%) fewer students today than in 2001, but this past year was the largest single-year dip on record. Despite this, per-pupil spending grew more than 5%.

When adjusted for inflation, per-pupil spending today is nearly 70% higher than twenty years ago, with little to show for it. Statewide test scores for Maine high schoolers, as well as graduation rates, have remained relatively stagnant over the last five years.

The governor, administration, and legislators should aim to scale back overall spending by targeting a per-pupil cost around $12,150, similar to that of the last fiscal year. This would ensure adequate funding for students and teachers, and free up at least $100 million to cover expected shortfalls and to relieve municipalities and taxpayers in the immediate future.

In 2019, Governor Mills’ and the Legislature allocated $300 million more to education than the previous biennium. This does not count the more than $337 million in federal funds spent through the state’s Coronavirus Relief Fund in the last year for meal delivery, protective gear, hand washing stations, classroom barriers, and more. In Mills’ latest proposal for FY22/23, education spending is slated to increase another $253 million. Has Maine noticed significant benefits to students from these decisions?

Much of Mills’ proposed increase to education is “baked in,” accounting for the $40,000 statewide minimum starting teacher salary legislators passed last session and the recently signed state employee contract, which guaranteed at least 3% yearly wage and salary increases. While the contract cannot change, lawmakers might consider removing the minimum teacher salary from statute. Allowing wage and salary rates to be determined through collective bargaining could remove yet another pressure point for state and municipal budgets.

There is still plenty of room for cost savings in Maine’s education system without disrupting funds dedicated to student instruction or teachers’ wages and benefits. System and school administration account for 8.4% of all education spending, or more than $290 million over the biennium. This does not account for transportation costs, student and staff support, special education, or other costs related to classroom instruction. Lawmakers should provide greater incentives for towns to promote smart reorganization and allow districts to pool resources and competitively bid for better vendor rates on supplies and services, including health insurance.

Unfortunately, last legislative session, Maine lawmakers severely restricted educational opportunity. Bills to permanently cap the number of charter schools at 10 and cap the amount of students virtual charters may enroll both passed and were signed into law by Governor Mills. Instead of doubling down on this cynical philosophy, lawmakers should recognize that more choice leads to better satisfied students and families. Maine should make it easier for education funds to travel with each student to the learning environment best suited to their needs, whether it be a public charter school, a virtual school, homeschooling, or a so-called “pandemic pod.” Maine should directly fund students, not institutions.

Maine could achieve greater flexibility for students and economize more than $20 million over the next biennium if only 1% of eligible students participated in a program similar to Arizona’s Educational Savings Account (ESA) program.

Since ESA-enrolled Arizona families receive 90% of the state share of per-student education funding, a study of the first eight years of the state’s program found that $600 goes to traditional public school districts for each enrollee. Because it does not take into account other public funds related to education like transportation reimbursement, facilities maintenance, and locally-approved property tax increases, as more students enroll in an ESA, average state per-pupil spending increases overall.

As overall student enrollment steadily declines, and per-pupil costs increase, Maine lawmakers would be wise to look at ways to make education funding more flexible, efficient and accountable to parental and student satisfaction. Instead of pursuing this strategy, the Mills administration modestly increases the amount of General Purpose Aid to local school districts, in order to ensure adequate staffing and protective equipment necessary to get teachers and students back into school.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MAINE SYSTEM

From 2019 to 2020, applications for federal financial aid from Maine high school seniors, also known as FAFSA forms, were down 12%. This phenomenon could be explained by the pandemic uncertainty, but it also demonstrates the ongoing shift away from youth seeking four-year college degrees. Ultimately, Maine will be sending fewer students to its institutions of higher learning as more forgo the contemporary college experience right after high school graduation. With fewer high-schoolers seeking an education through Maine’s universities, especially post-pandemic, now is the time to fully audit these costs to taxpayers.

Every year, Maine taxpayers are asked for no less funding for fewer and fewer students. Undergraduate enrollment in the University of Maine System (UMS)—excluding “Early College” students (highschoolers taking college courses)—dropped nearly 7% over the last five years. This includes double-digit enrollment losses at the Augusta (17.5%), Farmington (12.1%), Fort Kent (16.8%), and Machias (18.5%) campuses.

Over the last biennial budget, the University of Maine System received more than $400 million through the General Fund, 30% more than both New Hampshire and Massachusetts spend on higher education as a share of their budgets. This is a conservative number since Maine partially excludes tuition, fees, and employer contributions to health benefits and pensions in higher education expenditure reporting.27 By reducing taxpayer disbursements to the University of Maine System to levels comparable to our neighbors, lawmakers could return nearly $80 million to be used for the most critical state priorities.

In Governor Mills’ latest budget proposal, the administration proposes to flat fund UMS over the next biennium. While state leaders should be interested in a full audit of the university system’s balance sheet, one part of the budget proposal would diminish transparency and oversight of UMS borrowing. An aspect of Part PPP, the final section of the FY22/23 budget proposal, would exclude certain projects related to “capital lease obligations, financing for energy services projects or interim financing for capital projects” from legislative input. Maine law currently states that any borrowing exceeding $350 million in the “aggregate principal amount” must be submitted for legislative approval “at least 30 days before closing on such borrowing.” A UMS official confirmed to Maine Policy that this change would exempt borrowing for these projects from the statutory cap.

Maine taxpayers currently spend more than $16 million every year on debt service from UMS borrowing. Why should taxpayers and lawmakers have less oversight on this budget line? While UMS debt is not backed by the credit of the State of Maine, excluding certain projects from borrowing limits could facilitate a perverse incentive toward runaway spending and borrowing, leading to a weaker UMS credit rating and requiring greater financing from taxpayers. To avoid this potential pitfall, lawmakers should revise Part PPP of Gov. Mills’ budget proposal and remove this provision.

SPORTS BETTING

When New Hampshire legalized sports betting at the end of 2019 following a landmark Supreme Court ruling, nearly a dozen localities opted to allow it. According to Legal Sports Report, as of February 17, 2021, nearly $300 million had been spent on online sports gambling through DraftKings, which has an exclusive contract with the state. For that exclusivity, New Hampshire retains 50% of gross gaming revenue spent on the service. So far, state coffers have brought in more than $11 million from that agreement. Official estimates, which already appear to be too conservative, suggest that it will bring in $13.5 million in taxes by 2023.

There are Mainers who would participate in and profit from this sector of the economy but for Governor Mills’ decision to veto enabling legislation in January 2020. They will instead drive across the border to New Hampshire to bet on sports, either at a retail location or on their smartphone. Maine could have welcomed millions in economic growth and state tax revenue from allowing sports betting in 2020, ideally, through an open market of sports betting platforms. Especially during difficult and uncertain economic times, state leaders should not leave a potential industry (and its subsequent tax revenue) on the table.

HIGHWAY FUND

This analysis does not dive into the intricacies of the $232 million projected shortfall in Highway Fund, distinct from the more than $400 million General Fund biennial shortfall. Broadly, Maine lawmakers should ensure maintenance of critical infrastructure—roads, bridges, and ferries—before spending millions on “investments” in wasteful and anti-competitive energy and broadband projects.

Maine Representative Rich Cebra of Naples sponsored LD 43 in the 129th Legislature, which proposed to dedicate all sales tax revenue from sales of motor vehicles and goods related to motor vehicles to the Highway Fund for road and bridge maintenance. Over the last two fiscal years, including a brief period of depressed sales in March and April 2020, the Office of Tax Policy reports nearly $11 billion of taxable sales from “all transportation related retail outlets.” These sales brought in more than $500 million to the General Fund over the previous biennium. Dedicating less than half of these funds, or just the sales tax revenue from vehicle sales, could cover the entire Highway Fund shortfall.

CONCLUSION

Currently, the Maine state government is projected to face a nearly $400 million deficit over the next biennium. The good news is that this shortfall is less than half of what was initially projected in August 2020. There are other reasons to be hopeful that the economic costs of the pandemic-related shutdowns will not hinder long-term growth, but Maine has been facing impending, interrelated economic crises for decades: an aging labor force and an unfriendly overall business climate.

The proposals outlined here should be used to construct various pathways for legislators and the governor to achieve a balanced budget and a growing economy, not only for the next two years, but for the next two decades. Maine’s current economic situation is a precarious one, and the systemic issues previously mentioned will not simply fade away. These problems will only get worse the longer Maine lawmakers continue to delay bold action to provide a competitive economic environment, for business owners, workers, and potential entrepreneurs alike.

Instead of taking a long-term approach to crafting the state budget, Governor Mills is merely covering the next two years of costs with no guarantee that the levies will hold for the future. Her budget proposal largely relies on accounting gimmicks to maintain an elevated level of spending, driven in part by previous statutory commitments, but also by the baseline of her first budget. Two years ago, the governor grew real spending by 5% from the previous two years, even though the state’s population grew less than 1% over that time.

Over the last 10 years, real spending on Maine’s General Fund has grown more than 20%, while the population has grown by only 1.66%. Public spending should, at the very least, be tempered by population growth. Maine people deserve the most that their government can give them at the lowest cost, especially in difficult economic times.

Policy Reform & Projected Savings

Today, inflation-adjusted General Fund spending per Maine resident is $3,108, the highest on record. The last time it was closest to today’s height was in 2000, when the U.S. and Maine economies were experiencing the zenith of the 1990s boom. In the last three years of that decade, national GDP grew more than 4% annually. Needless to say, the vast uncertainty of the early 2020s presents a very different economic situation from the windfall of the late 1990s. If Maine lawmakers kept real spending on pace with population since 2010, per capita spending would only be $2,626. Taxpayers would have spent 18% less—$550 million—on the General Fund in the current fiscal year alone.

Today, inflation-adjusted General Fund spending per Maine resident is $3,108, the highest on record. The last time it was closest to today’s height was in 2000, when the U.S. and Maine economies were experiencing the zenith of the 1990s boom. In the last three years of that decade, national GDP grew more than 4% annually. Needless to say, the vast uncertainty of the early 2020s presents a very different economic situation from the windfall of the late 1990s. If Maine lawmakers kept real spending on pace with population since 2010, per capita spending would only be $2,626. Taxpayers would have spent 18% less—$550 million—on the General Fund in the current fiscal year alone.

Legislators should look to the findings in this report to make the hard choices that will put Maine on a path to real prosperity. The time is now to begin reining in ever-expansive government and plan for a future of sustainable growth and prosperity.